|

The Current Collection of News Articles from around the World, regarding The White River Monster.

|

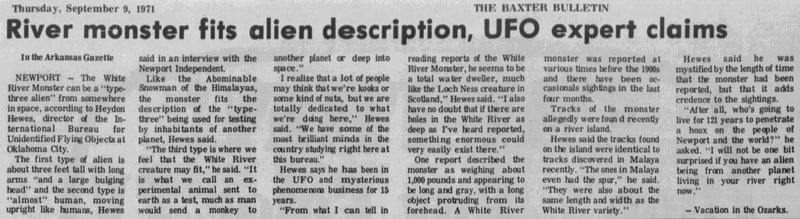

The first documented case of something strange in the river actually dates from December of 1912, an Arkansas newspaper reported that timber workers floating rafts of cedar on the White River below Branson, Missouri, had seen something large and strange on the bottom. At first they thought it was a boulder, but then they became convinced it was a gigantic turtle: They estimated its weight at 300 pounds. The report of the big river monster created quite a sensation among the sportsmen of Branson, and Tom Brainard, one of the local anglers, organized a party to go and capture it. As it will be impossible to gig the turtle they took a number of strong ropes which they will endeavor to loop over it and land it in that manner.

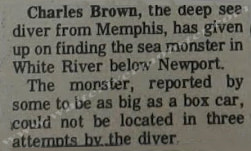

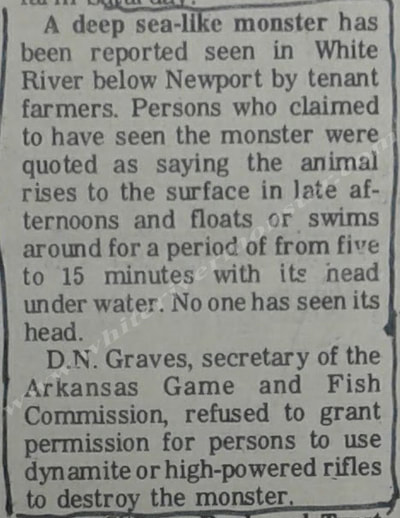

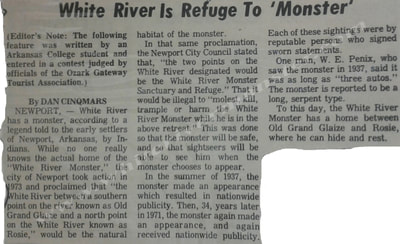

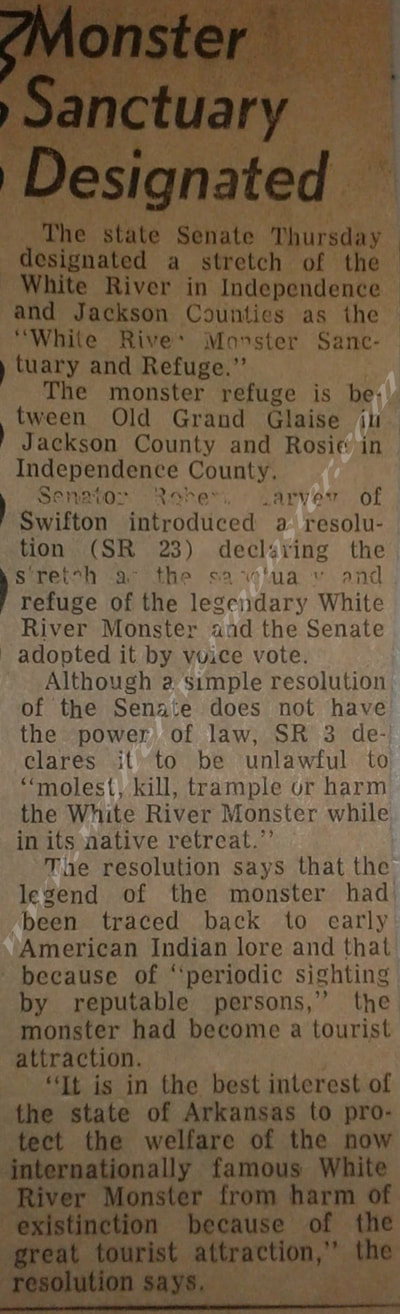

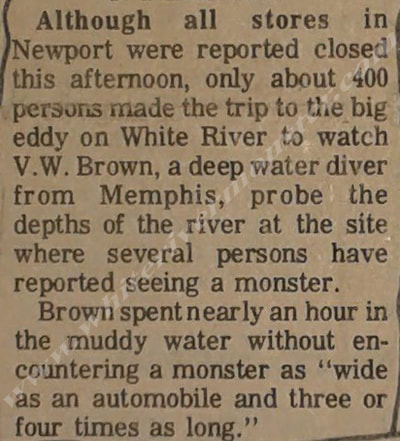

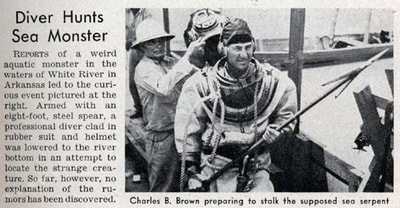

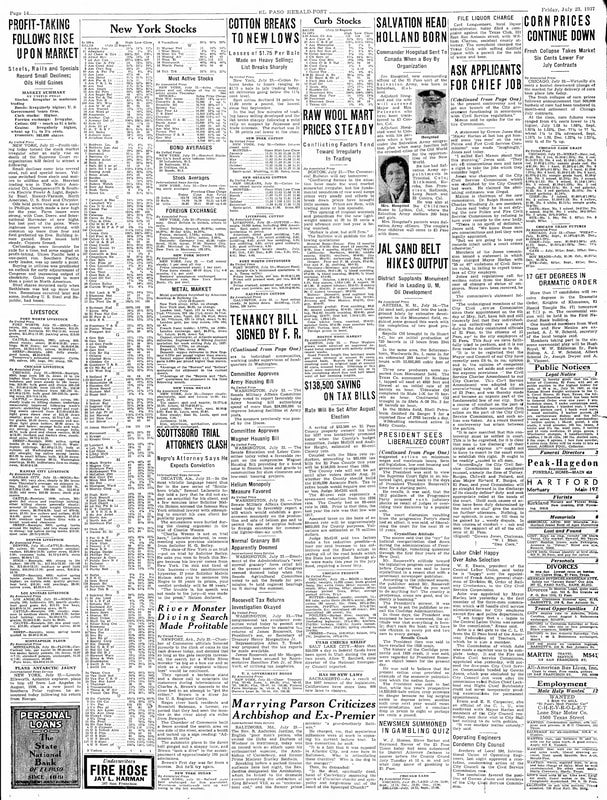

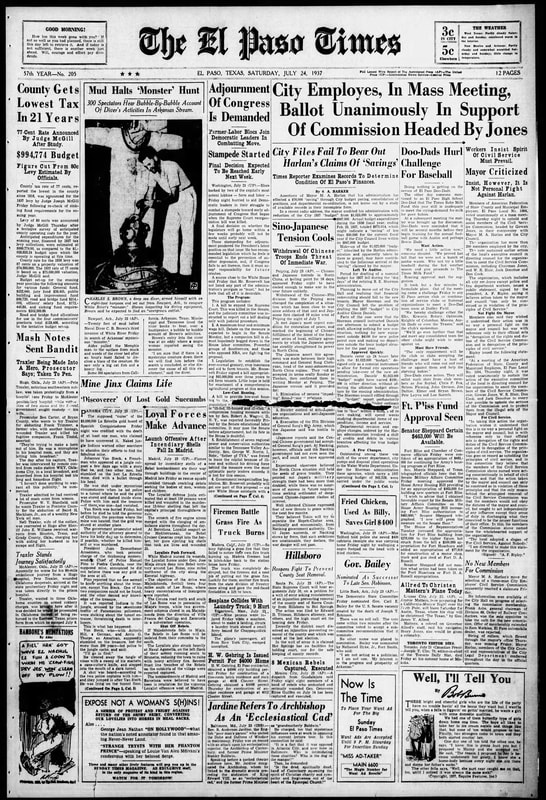

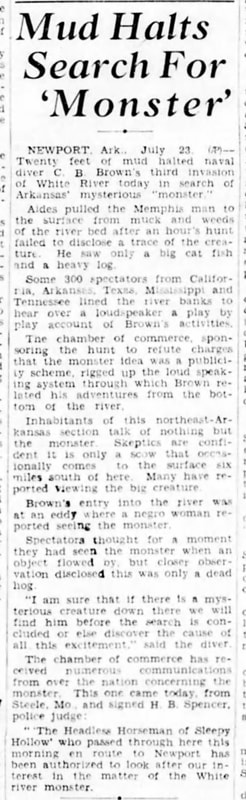

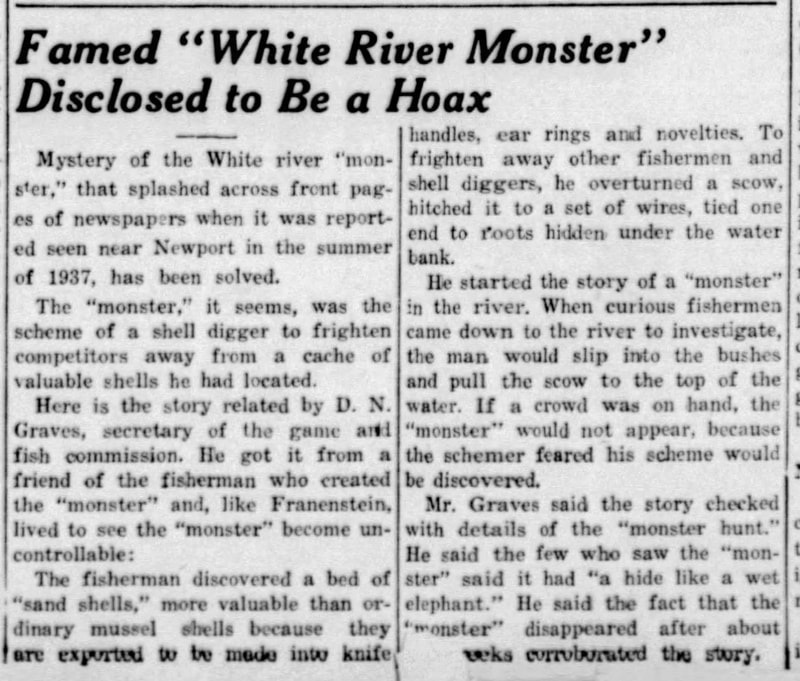

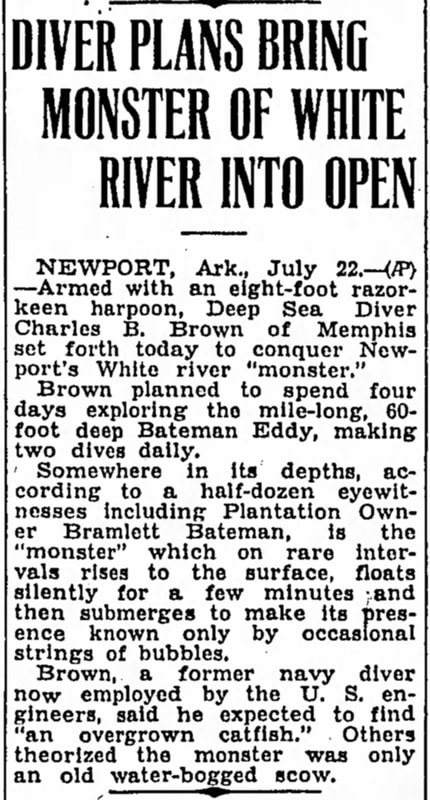

The story spread across the United States and by July 13, 1937, even the Trenton, New Jersey, carried the story of a state bridge toll collector’s effort to snag the beast: Newport residents fashioned a big rope net today in the hope of being able to snare a mysterious “monster” whose presence in a 60-foot deep White River eddy six miles south of here has frightened Negro plantation workers. W.E. Penix, State toll bridge collector, directing the net making activities, ordered it be constructed 40 feet long and 15 feet wide with meshes of six or eight inches. He estimated it would require a week or 10 days to complete the net and said a convoy of motorboats would sweep the eddy with it. Six days later news went out over the Associated Press that a “river bottom walker” was going after the monster. Hired by the local Chamber of Commerce, Charles B. Brown of the U.S. Engineer’s Office in Memphis reported that he did not expect to encounter anything dangerous in the White River, but would carry along a giant harpoon just in case. He was convinced the monster was a fish of some sort, most likely a giant catfish.

Time Magazine in 1937 reported…

One hot morning early in July the wife of Dee Wyatt, Negro sharecropper living on the banks of White River near Newport, Ark. shuffled out to her backyard pump, drew a bucket of water, groaned a mite as she paused to rest her back. Casually she glanced across the turgid river, then shrieked and scurried into the ramshackle house after her husband. Dee Wyatt popped his head out, took one look, and straightway headed for the home of Bramlett Bateman, nearest white farmer. He and his wife, he informed Farmer Bateman, had seen a monster. Neither of them had been drinking. Farmer Bateman skeptically stepped over to the river, then let out a whoop. Sure enough, there was a monster, “as big as a box car and as slick as a slimy elephant without legs.” Farmer Bateman rushed off to Newport, six miles away.

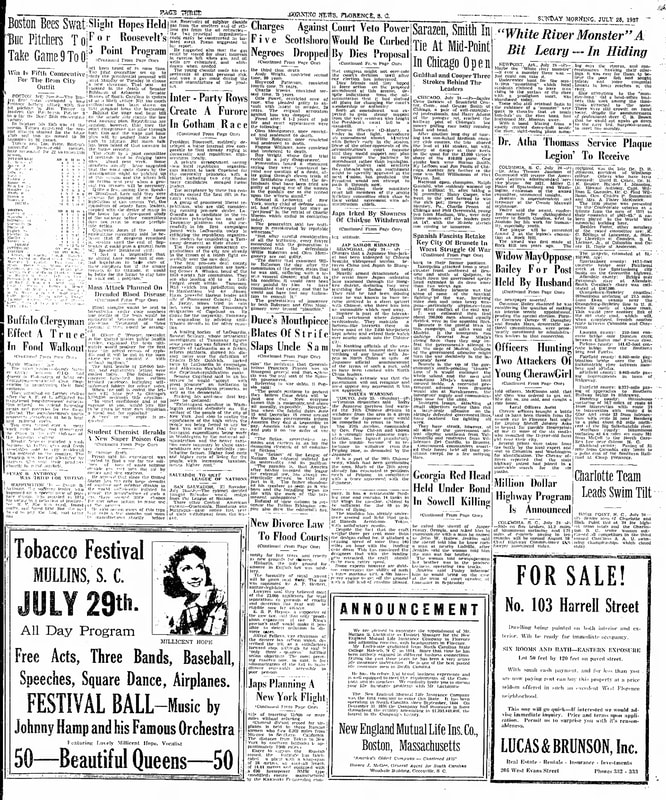

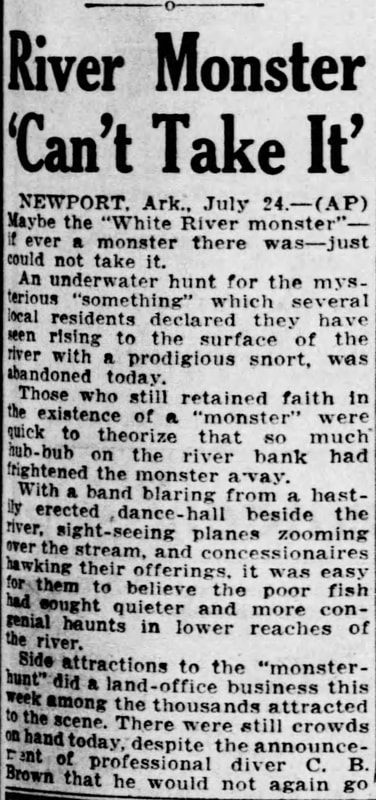

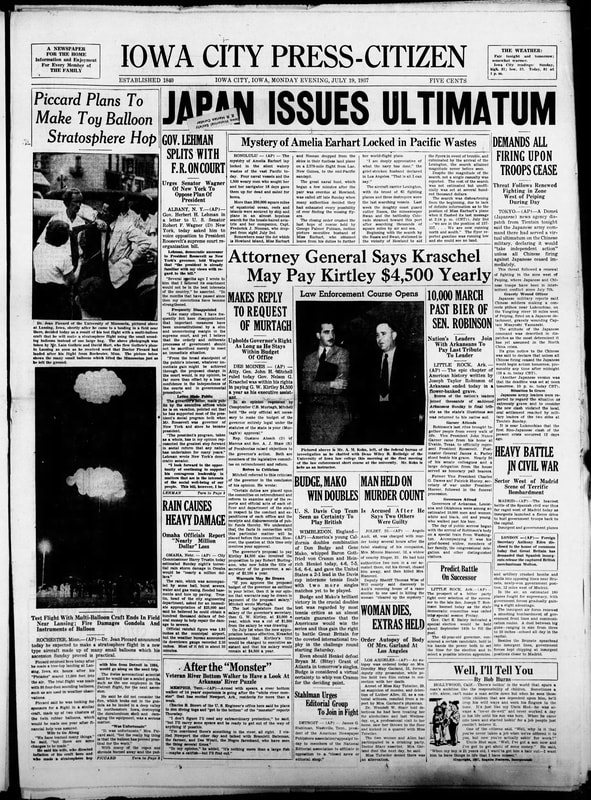

This White River story was warmly welcomed by the nation’s press, for 1937 has been a dull year for monsters. Preliminary indications were that Newport’s might be the monster-of-the-year. Twelve reputable citizens bore out Discoverers Bateman and Wyatt. Farmer Bateman and the Newport chamber of commerce built a fence around the viewing spot, charged 25¢ admission. Signs were tacked up on all roads—”This Way to the White River Monster.” The story skyrocketed when the chamber of commerce announced that Charles B. Brown, a diver from Memphis, had been hired to investigate at the spot the monster was seen.

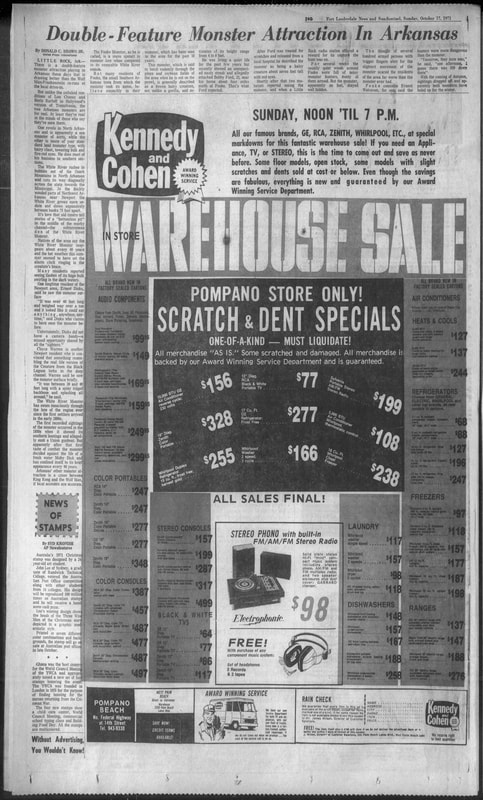

After talking to the discoverers, Diver Brown said, “In my opinion it’s nothing more than a large fish—maybe a catfish.” He had a razor-edged, eight-foot harpoon prepared. In Washington, the Bureau of Fisheries said it might be an alligator gar, which reputedly grows, sometimes, to be 20 ft. long. Other guesses: water-logged tree trunk, sunken barge, eruption of subterranean gases throwing up leaf accumulation, devil fish, sturgeon, or Old Blue, the legendary giant catfish of the Mississippi who every so often gets stuck in a canal lock or nudges in the bottom of a barge. As Diver Brown prepared for his first descent, Newport called an unofficial holiday. Lining the shore were hundreds of out-of-towners munching Farmer Bateman’s barbecued goat sandwiches and sipping his cold drinks. A loudspeaker was erected and after much ado on the great morning, Diver Brown went down into the swirling river, rendered muddier than usual by recent rains. He reported that visibility was only three inches, came up after 75 minutes of fumbling around. In the afternoon he descended again, returned with no report. Far into the night spectators amused themselves at a “Monster Dance” beneath flickering lamps. Next day attendance fell off, but Diver Brown descended again. When an air valve jammed in the helmet of his diving suit, he popped unexpectedly to the surface, still having seen nothing. By this time the crowds had melted completely away and so, presently, did Diver Brown.

The story spread across the United States and by July 13, 1937, even the Trenton, New Jersey, carried the story of a state bridge toll collector’s effort to snag the beast: Newport residents fashioned a big rope net today in the hope of being able to snare a mysterious “monster” whose presence in a 60-foot deep White River eddy six miles south of here has frightened Negro plantation workers. W.E. Penix, State toll bridge collector, directing the net making activities, ordered it be constructed 40 feet long and 15 feet wide with meshes of six or eight inches. He estimated it would require a week or 10 days to complete the net and said a convoy of motorboats would sweep the eddy with it. Six days later news went out over the Associated Press that a “river bottom walker” was going after the monster. Hired by the local Chamber of Commerce, Charles B. Brown of the U.S. Engineer’s Office in Memphis reported that he did not expect to encounter anything dangerous in the White River, but would carry along a giant harpoon just in case. He was convinced the monster was a fish of some sort, most likely a giant catfish.

Time Magazine in 1937 reported…

One hot morning early in July the wife of Dee Wyatt, Negro sharecropper living on the banks of White River near Newport, Ark. shuffled out to her backyard pump, drew a bucket of water, groaned a mite as she paused to rest her back. Casually she glanced across the turgid river, then shrieked and scurried into the ramshackle house after her husband. Dee Wyatt popped his head out, took one look, and straightway headed for the home of Bramlett Bateman, nearest white farmer. He and his wife, he informed Farmer Bateman, had seen a monster. Neither of them had been drinking. Farmer Bateman skeptically stepped over to the river, then let out a whoop. Sure enough, there was a monster, “as big as a box car and as slick as a slimy elephant without legs.” Farmer Bateman rushed off to Newport, six miles away.

This White River story was warmly welcomed by the nation’s press, for 1937 has been a dull year for monsters. Preliminary indications were that Newport’s might be the monster-of-the-year. Twelve reputable citizens bore out Discoverers Bateman and Wyatt. Farmer Bateman and the Newport chamber of commerce built a fence around the viewing spot, charged 25¢ admission. Signs were tacked up on all roads—”This Way to the White River Monster.” The story skyrocketed when the chamber of commerce announced that Charles B. Brown, a diver from Memphis, had been hired to investigate at the spot the monster was seen.

After talking to the discoverers, Diver Brown said, “In my opinion it’s nothing more than a large fish—maybe a catfish.” He had a razor-edged, eight-foot harpoon prepared. In Washington, the Bureau of Fisheries said it might be an alligator gar, which reputedly grows, sometimes, to be 20 ft. long. Other guesses: water-logged tree trunk, sunken barge, eruption of subterranean gases throwing up leaf accumulation, devil fish, sturgeon, or Old Blue, the legendary giant catfish of the Mississippi who every so often gets stuck in a canal lock or nudges in the bottom of a barge. As Diver Brown prepared for his first descent, Newport called an unofficial holiday. Lining the shore were hundreds of out-of-towners munching Farmer Bateman’s barbecued goat sandwiches and sipping his cold drinks. A loudspeaker was erected and after much ado on the great morning, Diver Brown went down into the swirling river, rendered muddier than usual by recent rains. He reported that visibility was only three inches, came up after 75 minutes of fumbling around. In the afternoon he descended again, returned with no report. Far into the night spectators amused themselves at a “Monster Dance” beneath flickering lamps. Next day attendance fell off, but Diver Brown descended again. When an air valve jammed in the helmet of his diving suit, he popped unexpectedly to the surface, still having seen nothing. By this time the crowds had melted completely away and so, presently, did Diver Brown.